MRV and More New Ways of Marketing Food in Agriculture

Scoring fieldwork for ecological market credentials is part of the monetization process for active restoration of farmland.

There is a new language coming together to match up environmental concerns with production agriculture. It might seem silly, and daunting, to conventional grain marketers especially. It’s also highly unfamiliar, since none of the new attributes that buyers are seeking are accounted for in the current grading systems.

Few people wake up one day and decide to learn a new language. It’s not easy.

But when stuck in a foreign country, most people learn enough of a new language to survive.

Some people will master that new language, and conform to the new culture. For their efforts, these individuals experience personal growth and success in a new landscape.

This research series covers topics around how carbon markets are clashing with commodity markets. Farmland management economics are shifting already with new government payments, and new attribute valuations will be next. One example is carbon payments.

The news around carbon markets is bleak these days, to be sure. New reports keep surfacing about false claims and over-reporting. There seem to be two main factors behind these cases, the first being emotional: human greed and the defensiveness of the biggest corporate emitters.

The second factor highlighting so many cases of misrepresented value in carbon pricing is advances in the technology for calculating impacts. When the early voluntary carbon markets were launched, predictions had to be made around the volumes of carbon that would avoid being emitted and/or stored by the projects generating the credits. Now in the auditing phase, the initial predictions, promises, and values turned out to be overstated.

The technological advances that are now working to expose the shortcomings of carbon pricing and climate finance platforms are happening in a new sector called MRV (measurement, reporting, validation). MRV is also the backbone of traceability in food.

Monitoring is the need for companies - including farms - to pay attention to their environmental impact in doing business.

Reporting is the transparency provided to everyone else in the supply chain - including consumers.

Validation is the ability to prove that nobody who’s reporting these metrics is lying (greenwashing).

The global food industry is highly concentrated. Less than ten huge consumer packaged goods (CPG) corporations each own many individual food brands, and produce the vast majority of the food stocked in grocery stores. An equally small number of massive wholesale businesses provide distribution for these brands to the grocery outlets. The food CPG companies buy their ingredients from another very small number of very large commodity corporations. These commodity buyers form the marketplace for nearly all of the world’s individual farms.

It is through this maze that consumers and investors attempt to flow purchasing power and impact finance as incentives for less intensive farming practices. The market for certified organic foods is an example of additional financial opportunity for farming practices that some consumers believe to be better for the environment.

The money and momentum in regenerative agriculture is much, much greater than anything ever seen before, including certified organic and the natural food products category overall. Now we have oil and gas and fertilizer companies at the table with their wallets out hoping to connect with farmers too. And as new ESG (environmental, social, governance) reporting requirements become part of securities exchange reporting and compliance, public markets are coming to the table next.

Because the potential for regenerative agriculture as a climate solution is enormous, everybody wants in. And even though that can make a mess at times of how the work is valued, it’s still a good thing.

Every failure is feedback, including the market failure that best describes early carbon trading initiatives. We now understand that linear mechanisms and biased estimations don’t work to properly value ecology-supporting credits. And we know a lot more about the common principles that the purchasers of these credits are driven by.

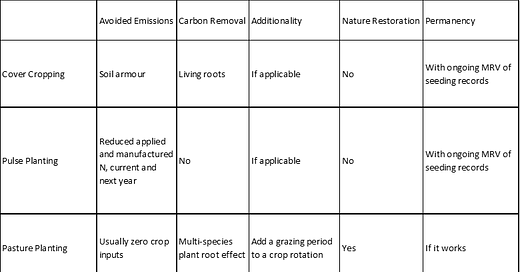

For example, some of the outcomes that count as carbon and ecosystems market credentials that we can work with include:

Avoided emissions

Carbon removal

Additionality

Nature restoration

Permanence

Turning once again to the data model that is now available in Canada in the form of the On Farm Climate Action Fund (OFCAF), the table below compares some of the funded field activities to the above credentials. Under each credential, the way that the outcomes occur and are validated is noted.

The purpose of the above is to illustrate the potential for additional credit market-generated payments to be earned by Canadian OFCAF-approved farms, for activities that fit the principles driving the demand for offsets. The more credentials that a practice can offer, the more valuable will be its data validation to the market in the future.

The crux of this whole matter is at what point will these additional layers of value make it worthwhile for the commodity handlers, processors, and distributors to segregate food ingredients with these attributes, so that the CPG brands can count them in their scores? There are precedents that businesses can draw from, to help lay out the math and next steps for handling and segregating products with the additional attributes discussed here.

For example, conscious consumers long ago established a demand segment for certified organic foods that eventually commodified, creating efficiencies in production, handling and distribution, enabling segregation and paper-based traceability at a reasonable cost. Other examples include non-GMO canola and soybeans, the Warburton wheat program, and malting barley.