Re-Imagining Trade Channels

Local, farm-branded foods move to market in a totally different system of supply chain components, compared to commodity foods. As the latter face new market threats, the former's is expanding.

At the end of the day, whatever ends up being the exact costs of new tariffs on agricultural imports, exports and food, producers and consumers on the commodity side are worse off than before. Meanwhile, new money is headed to local food production, handling and distribution infrastructure, and in removing barriers to internal trade.

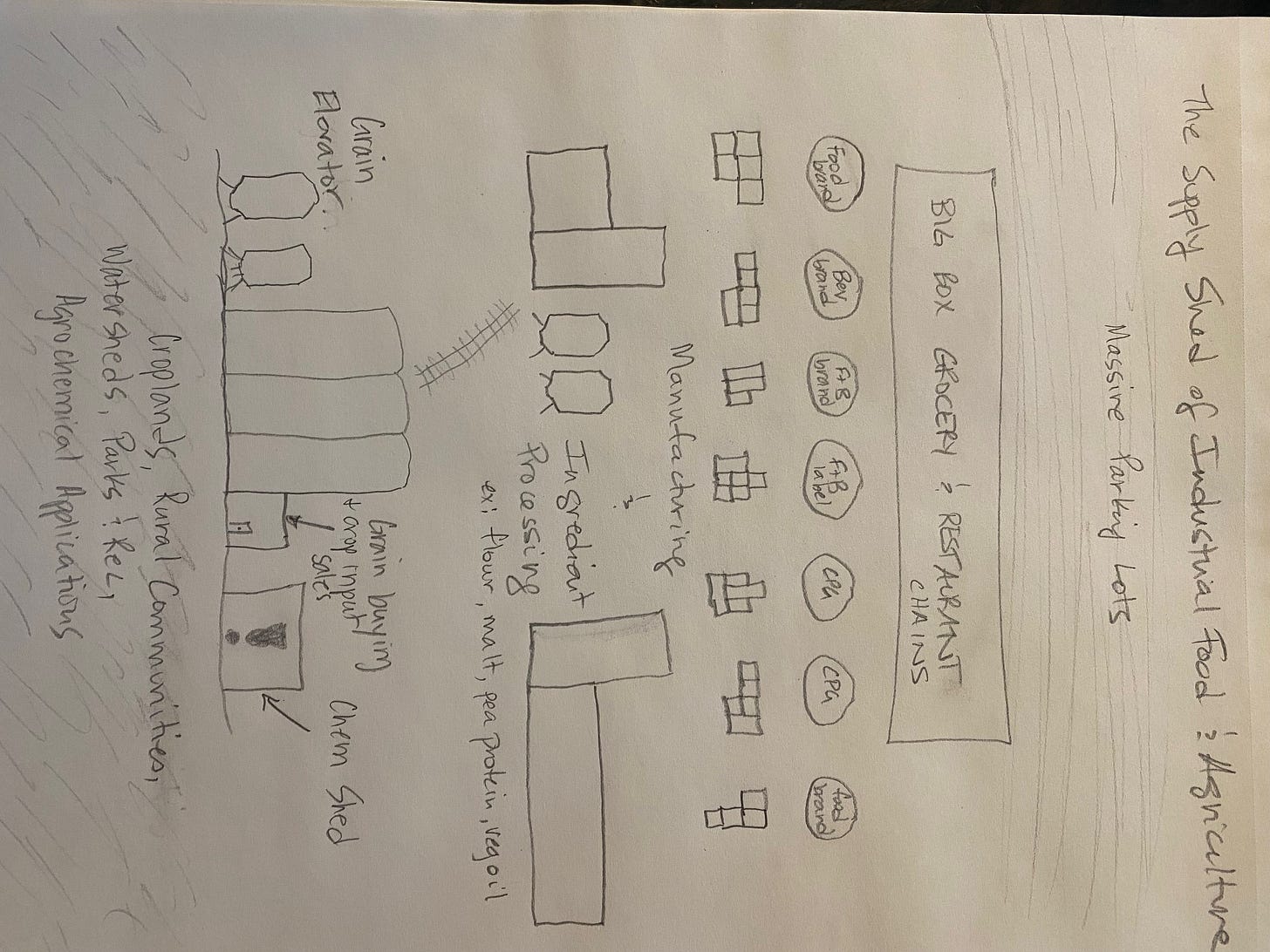

According to this comprehensive guide for greenhouse gas accounting and reporting put out by Value Change, “supply sheds are a group of suppliers in a specifically defined market providing similar goods and services.” Notice how in the illustration of grain ingredient sourcing in industrial food and agriculture, the links in the chain are linear, and can be extended very long distances.

From Subway to Red Lobster; breakfast cereal to red meats, big-box food sales are funneled from the same model. Wholesale distributors fill back-of-house inventories for rotating products into shelves or plates on a first-in-first-out basis.

Customers arrive in expansive concrete parking lots to purchase a selection of CPG food brands; heavily packaged and labeled; tracked with lot numbers. The ingredients that make up these goods come from industrial processing plants like flour mills, malt houses, high-fructose corn syrup, oilseed crushing and refineries, and pea fractionation facilities.

Industrial processing plants purchase their raw ingredients from grain companies, who in turn buy from farmers. Sometimes those grain companies also sell crop inputs, aka agrochemicals, which may be considered a conflict of interest.

In Supply Chains,

Scope 3 emissions cascade down from raw ingredient production, through distribution, manufacturing and then broadly across the major food brands that source grains and oilseeds from commodity agribusiness.

Supply chains are built on isolated transactions. Each company might buy and sell to multiple other companies, but they don’t share information.

The distances that industrial food travels in a supply chain are very long, and connections between producers, handlers, processors and consumers are erased.

Food Webs, By Contrast

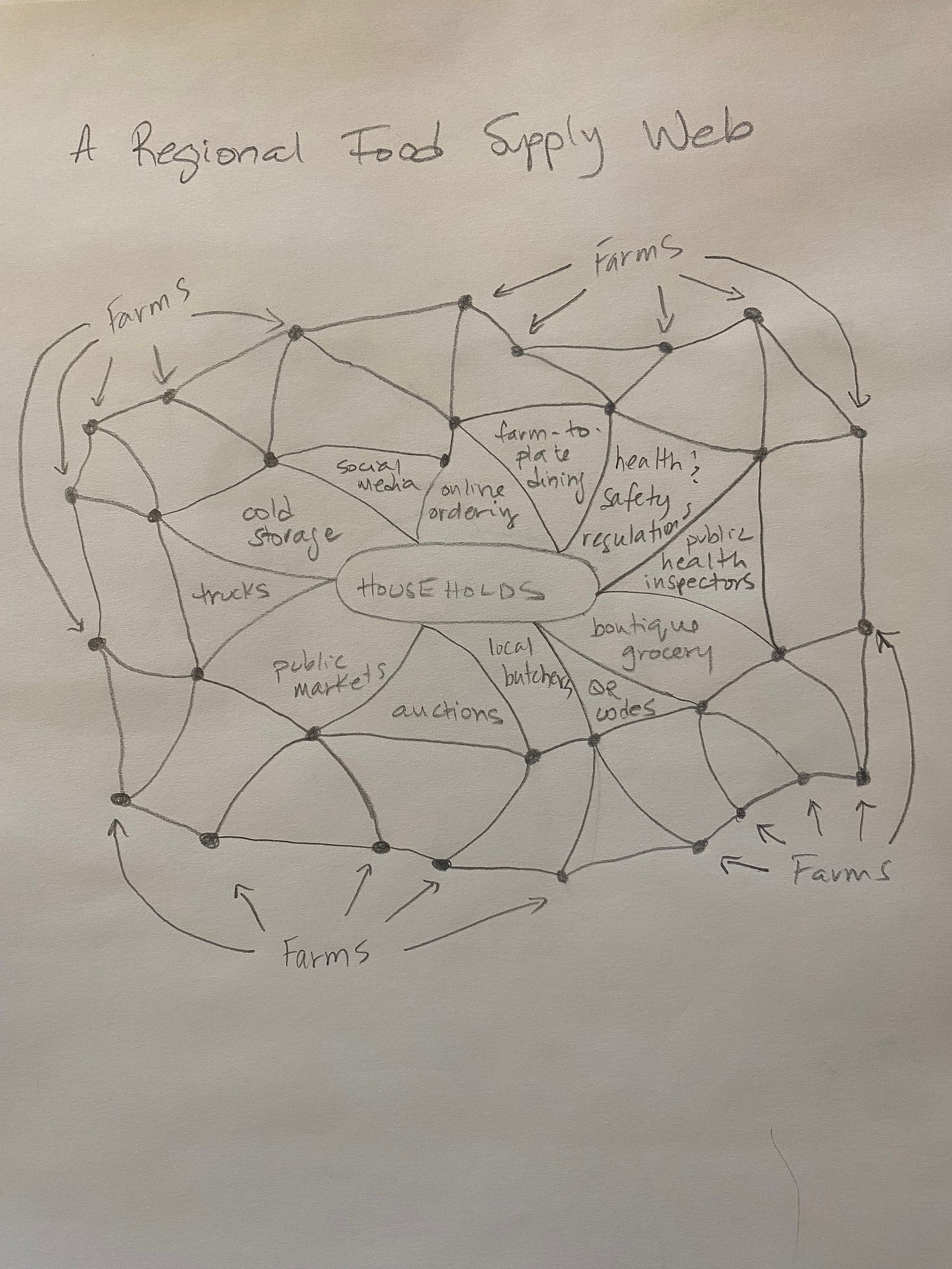

National Geographic defines a food web as “a detailed description of the species within a community and their relationships with each other, showing how energy is transferred up food chains that are interlinked with other food chains.”

Food webs still rely on a system of production, processing and distribution in order to supply households with foods, but it looks totally different. The players in between farms and food customers are smaller, regional, and interact like this:

Households form the center of food web economies because they are central to fueling growth and supporting resiliency of the best farmers. Farms can connect individually into food webs by establishing connections with all the providers of processing, distribution and marketing necessary to sell into households.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Prairie Routes Research to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.