Sheds & Webs

While more people question the sprawling suburbs serving food to households in and outside of cities, interconnectivity is building in short-chain regional food webs.

Major food brands are making aggressive commitments to reduce their supply shed emissions and total environmental footprints, back to the original source of all ingredient production. Most are finding it difficult to gain a full view back through the food and agriculture industry, but once they do, agrochemical field applications are found to be the biggest culprit.

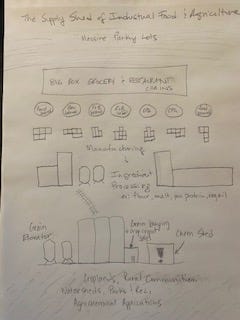

According to this comprehensive guide for greenhouse gas accounting and reporting put out by Value Change, “supply sheds are a group of suppliers in a specifically defined geography and/or market providing similar goods and services that can be demonstrated to be associated with the company’s value chain.” Here’s what it looks like in grain ingredients sourced through the industrial food and agriculture supply chain:

From Subway to Red Lobster; breakfast cereal to red meats, big-box food sales are funneled from the same model. Wholesale distributors fill back-of-house inventories for rotating products into shelves or plates on a first-in-first-out basis.

Customers arrive in expansive concrete parking lots to purchase a selection of food and beverage brands. Manufacturing of CPG foods creates packages in a box-like set of processes tracked with lot-numbers. The ingredients that make up these goods come from industrial processing plants, like flour mills, malt houses, high-fructose corn syrup, oilseed crushing and refineries, and pea fractionation facilities.

Industrial processing plants purchase their raw ingredients from grain companies, who in turn buy directly from farmers. Sometimes those grain companies also sell crop inputs, aka agrochemicals, which may be considered a conflict of interest.

In Supply Sheds,

Food chains are linear and emissions cascade down from distribution, manufacturing and then broadly across the croplands that rely on intensive production methods to produce the raw ingredients.

Supply chains are built on isolated transactions. Each company might buy and sell to multiple other companies, but they don’t share information or the consequences of external impacts.

The distances that foods travel are almost impossible to track, and connections between primary producers and end product consumers are completely erased.

Food Webs, By Contrast

National Geographic defines a food web as “a detailed description of the species within a community and their relationships with each other, showing how energy is transferred up food chains that are interlinked with other food chains.”

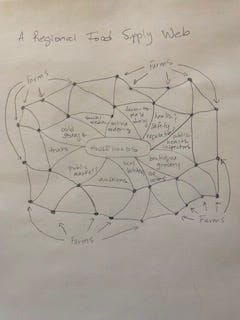

Food webs still rely on a system of production, processing and distribution in order to supply households with foods, but it looks totally different. The players in between farms and food customers are smaller, regional, and interact like this:

Households form the center of food web economies because they are central to fueling growth and supporting resiliency of the best farmers. Many farms can supply into a food web by establishing connections with all the providers of processing, distribution and marketing necessary to sell directly to households.

For the purpose of this research, ‘farms’ are defined as operations that use land to grow food to feed people. ‘The best farms’ create an environment around the area used to produce the food that is regenerating (as opposed to degenerating).

Webs - more so than chains - are structured to link outcomes into foods, and are beautiful in their complexity. They link farms to households via public markets, online ordering, freezer trucks, health and safety inspectors, auctions, boutique grocers, QR codes, and social media outlets, restoring connection and accountability throughout the community of stakeholders.

Summary

Marketing is said to be the hardest job for every type of farmer. Direct marketers have to build an entire customer base, while balancing the unpredictability of supply and demand, amid a capacity-limited supply chain.

Commodity farmers face futures market volatility and heavy stress in choosing the time and place to sell their crops. Cash contract terms can be confusing, adding to the pressure in making marketing decisions, which ultimately form the farm’s revenue stream.

None of these considerations are behind the agriculture and food industry’s move towards transparency and reduced agrochemical use. Yet it is squarely in the interface between the farm and its buyers, i.e. in marketing, that the economic impact of the need to shift farmland management decisions will be felt.

Webs are sticky, while sheds are drafty. When it comes to catching hold of negative environmental externalities and factoring them into farm market prices, the two systems are polar opposites.